Critical Media

After its debut in 1996, the TV station al-Jazeera received praise for democratizing the media in Arab-speaking countries and quickly became a fixture among Arab viewers for its taboo-breaking reporting. After September 11, however, criticism mounted, particularly in the United States, that the Qatar-based station was anti-American and pro-terrorist – for its unflattering coverage of U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, its broadcast of several hours of tape from Osama bin Laden, and its outspoken and sometimes anti-American talk show hosts.

These perceptions of the station prompted U.S. soldiers in Iraq to arrest and beat several reporters, and the Iraqi and Bahraini governments to ban the station’s broadcasts. But al-Jazeera is far from a mouthpiece for al-Qaeda. For instance, it broadcast 500 hours of press statements from George W. Bush and interviewed the likes of Condoleezza Rice, Donald Rumsfeld, Tony Blair, and Ariel Sharon.

The controversy over its coverage of U.S. policy has obscured how innovative the television station has been: broadcasting 24 hours with live reports, sponsoring uncensored talk shows, covering cultural issues that other media in the Arab world avoid. Al-Jazeera is not exactly a grass-roots alternative media outlet. After all, it’s owned by Qatar’s emir, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani. But it has consistently provided an alternative and independent voice in an arena dominated by conservative Arab-language stations and foreign conglomerates that have a history of ignoring the political subtleties and cultural sensibilities of the Arab world. The station is branching out with a sports channel, a children’s channel, and a live conference channel that resembles C-Span. Al Jazeera International, the English-language version to be launched in 2006, will draw on the talents of former BBC, CNN, and Sky News journalists. What started out as an alternative voice is fast becomingthe source of news in the Arab world.

Despite the aspirations of CNN or the International Herald Tribune, there is no global media standard. A great deal depends on political culture. French newspapers are affiliated with particular political positions; U.S. newspapers for the most part claim objectivity and neutrality; there is no independent media in North Korea. Even the claim that all journalism must be objective is undermined by choice of coverage, language of presentation, selection of voices for the opinion page, degree of access to government sources, and so on. To a certain degree, these issues of content can be traced back to issues of control: who owns the presses and the stations and the bandwidth. In this regard, the mass media has moved in two contrary directions in recent years – toward greater corporate concentration and toward greater public access. From 1983 to 1997, according to Ben Bagdikian, the number of dominant firms in control of the media shrank from 50 to ten. This corporate control of the major media outlets has affected coverage in both subtle and overt ways. Now that Disney owns ABC, the television station is loathe to criticize the Magic Kingdom.

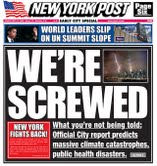

Yet, even as mergers and acquisitions concentrate the levers of the information industry in fewer and fewer hands, there has been an explosion of new, grassroots media. Liberal bloggers like Daily KOS and Atrios compete with conservatives like Matt Drudge (the Drudge Report) to spin the news and influence policy. Hacker-jesters like The Yes Men are patrolling the fine line between satire and libel to leverage their media appearances into anti-corporate buzz. Digital video makers, pirate radio deejays, and public access TV producers are chronicling realities that the mainstream won’t (at least initially) touch. In some cases, alternative media has helped to bring down dictators, as B-92 radio did in Serbia. In other cases, the new media serves the more modest function of watchdogging the watchdogs, with websites and bloggers subjecting CNN, The New York Times and other organs of mainstream journalism to the kind of scrutiny that was once the sole province of the Columbia Journalism Review and its ilk.

If objectivity is largely a chimera, what other principle can guide journalistic practice? What kind of future public policy can we expect in a world where, as Neil Postman has argued, the presentation of all information is tending toward spectacle and entertainment? While the barriers preventing access to mass media have decreased as a result of new technologies, how useful is all the new information if no one has the time to read and process it? Are there any spin-free zones? Is TV news an oxymoron? Is National Public Radio a liberal haven in a conservative media or an increasingly conservative voice that mirrors the political realities of 21st century America? Is the mainstream news media in the United States moving further to the right in general?

On a trip to Provisions, you can read about Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman and her quest for the real scoop in The Exception to the Rulers, find out what the media left out of the big stories in the magazine Extra!, log on for the essence of grass-roots journalism at Plastic, listen to spoken word from the former Dead Kennedy Jello Biafra on his Become the Media CD, and see bias in action in the critique of Fox News in the movie Outfoxed.