Youth Activism

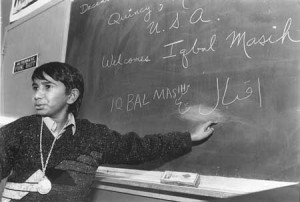

At the age of four, Iqbal Masih was sold by his father to the owner of a Pakistani carpet factory for $200. Over the next six years, for as many as 12 hours a day, Iqbal worked the looms and suffered verbal and physical abuse. In 1992, at the age of ten, he attended a meeting of the Bonded Labor Liberation Front (BLLF) and, after listening to the presentations and giving eloquent testimony about his own experiences, decided not to return to the factory.

One of an estimated 20 million bonded laborers in Pakistan, Iqbal became an international spokesperson for the BLLF and was responsible for freeing as many as 3,000 Pakistani children. He also called for a boycott of Pakistani carpets. As a result of these and other actions, he was targeted by Pakistani carpet manufacturers and received a number of death threats. In 1995, unknown assailants gunned Iqbal Masih down at the age of thirteen.

The political and social activism of young people did not begin in Seattle in 1999 or on American college campuses in the 1960s. Young people took the lead in the 1848 revolutions in Europe as well as the 1989 transformations in Warsaw, Prague, and Berlin. Young people were instrumental in Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement and in the huge May 1 demonstration in Korea in 1919. In 1937, the first major march on the White House attracted thousands of young people who protested the conditions of impoverished youth.

Youth activism has been a critical component – and often a leading force – in many of the important social movements in modern history. Young people spearheaded ACT-UP, a group formed to shake up the political and medical worlds to address the issue of HIV-AIDS. A “third wave” of young feminists is revitalizing the women’s movement. Hip-hop music, new generation poetry, punk politics, anarchist organizing, wired hackers, Do-It-Yourself philosophy, and ‘zine aesthetics are constantly remaking alternative culture. Young activists have been at the forefront of the global anti-war movement, from Vietnam to Iraq, have organized against military recruiters, and have pushed for the right of conscientious objection throughout the world. And young people have galvanized the global justice movement by launching an anti-sweatshop campaign at Duke University in 1998 and helping to organize not only the “battle in Seattle” around the 1999 WTO ministerial but subsequent protests in Cancun, Quebec and Genoa.

Have young activists managed to organize across class lines – between “town” and “gown”, between urban and suburban, between the global North and the global South? Are youth movements restricted by the inevitable aging of their members? To what extent are “youth issues” such as child labor or child soldiers put forward by youth movements? And given the global popularity of MTV, video games, and other consumer pursuits, how representative of youth in general is the latest wave of young activists?

On a trip to Provisions, check out the most dynamic youth activists in the United States in the book Future 500, leaf through the articles on music and politics in the magazine Punk Planet, watch the DVD of Rage Against the Machine’s concert in Mexico City with its bonus feature on Mesoamerican politics, listen to the latest CD Black Dialogue by hip-hop group The Perceptionists and its scathing track on the war in Iraq entitled “Memorial Day,” surf the latest information about feminism on campus, and thumb through the pictures of extraordinary stencil art from South Africa to Argentina to downtown Chicago in Josh MacPhee’s Stencil Pirates.